Palm Fronds: Found Wood

By Bill Einsig

Thanks to Chet Wilcox, Bob Sutton, Del Herbert, and Anthony Donato for their support and advice in preparing this text.

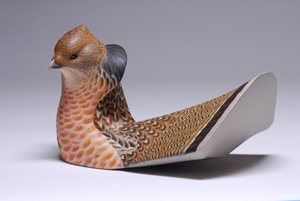

Bob Sutton carved this palm frond Pintail in the early 1980s. It belonged to Bebe Hopper until 2008 when she brought it to Cal Open as a donation to the club's auction. However, it never made it to the auction but was purchased on sight by a collector attending the show.

|

|

|

Ever carve a pintail from a leaf stem? For much of the last century, California waterfowlers did just that.

Photo 2

Always in search of inexpensive, easy-to-find materials for working decoys, hunters discovered they could fashion effective decoys from the enlarged base of the palm leaf. These dekes were light in weight, buoyant, and easy to make with a bit of shaping, a carved wooden head, and a few weights. The porous material soaked water like a sponge, and they lasted for only a season or two. But the heads and weights could be salvaged from a damaged bird and placed on new bodies shaped from the easy-to-find leaf litter dropped from date palms. But first, a bit of biological background for inquisitive carvers. Botanists organize all flowering plants into two subgroups: monocots and dicots. While the basic characteristic for this grouping is the number of embryonic food storage areas in the mature seed, monocots and dicots have many other differences as well. One of these, stem structure, is of particular interest to carvers. Woody dicots, like oak, hickory, tupelo, pine, and thousands of other species, have stems with a growth layer (cambium) that forms annual rings of food- and water-conducting vessels. The tubes within these rings become rigid with cellulose and lignin forming the "wood" carvers know so well. These annual rings also form the "grain" typical of woody dicots. Monocots, like palm, corn, grass, lilies, and thousands of other species, typically lack the cambium in their stems. Rather than forming a series of concentric rings, the conducting tubes in a monocot are arranged as separate and distinct bundles of fibers and tubes. These "fibrovascular" bundles are then scattered throughout softer tissue within the stem. Think of a corn stalk filled with soft inner tissue and scattered fibrous, strings (bundles) throughout the stem. Bundles are close and tightly packed on the outside edge forming an outer epidermis that can be quite rigid providing the primary structural support for the plant. The palm leaf stem is similar: hard surface (epidermis) on the outside due to closely packed, dense fibers, but soft like balsa on the inside where fibrous bundles are scattered through softer tissue. Hit this with a power grinder and you'll be glad you're wearing a dust mask. Chet Wilcox says he collects date palms that are common in California and other areas of the Southwest, but they are not native to North America. Date palms originate in the arid countries of North Africa, Middle East, and Near East in, perhaps, what was once the Fertile Crescent—the cradle of life. By the 1700s, date palms were brought to the American Southwest where they were cultured for their delicious fruit. Today, there are numerous varieties grown for fruit and ornamental uses. In comparison to North American native trees, date palm leaves (fronds) are huge. They average 10-12 feet in length but can be much longer. They live for 5-6 years, on average, and often hang from the base of the leafy crown for several years where they are weathered by wind and rain before they eventually fall. If the trees are cared for, as in ornamental or cultivated areas, dead leaves are pruned and discarded. Palm leaves are compound giants with numerous leaflets arrayed along opposite sides of the main stem, or midrib. This arrangement is "pinnate" because it resembles the structure of a flight feather. The typical leaf has a zone above the base with no leaflets. This zone is followed by a short section of spines, or thorns, arising along opposite sides of the midrib. There may be fewer than a dozen or more than four dozen spines. Individual thorns can be up to 10 inches in length and one-half inch in diameter. Finally, above the spine zone, up to two hundred leaflets line opposite sides of the palm leaf. The part of this leaf used by decoy carvers is the thickened base of the midrib. This thickened petiole is actually part of, and grows from, a fibrous sheath that surrounds the palm trunk. However, the leaf is typically cut from the sheath, or naturally separates from it, when the leaf drops.

Photo 3

Chet Wilcox, Wil-Cut Company, is one of the few carving suppliers who offer fronds to carvers who want to experience this form of traditional decoy carving. Chet chooses quality stems, trims them to length, size, and shape, and removes the treacherous spines. In comparison to other carving woods, palm fronds are very inexpensive and Chet maintains a healthy inventory. Carving a decoy from a frond, however, is not for everyone. If you're the "draftsman" carver dependent on patterns and detailed measurements, palm frond carving could be a refreshing change. Rather than following carefully detailed steps, the palm frond approach is far more spontaneous and artistic. The frond offers a basic shape, but each carver relies on innate creativity to bring the bird from that chunk of palm. No two palm frond carvings are alike, and that's their charm.

|

|

Contact Chet Wilcox at 916.961.5400 for palm frond availability and pricing.

Read more about Palm Fronds... An Ohioan's First Foray into Palm Frond Carving

|

| Palm fronds up close... | |

Photo 4

|

Photo 5

|

|

The enlarged base of this palm leaf is in the foreground on the right. The leaf, far too large to completely fit into the photograph, extends to the left, then bends back to the right. Even so, much of the leaf has been cut away. Notice the zones on the leaf base. There is a zone with no leaflets or spines followed by a zone of long spines. |

Here, the camera moves just a bit to the left.The zone of spines is clear in the foreground, andleaflets are clear in the background. Suppliers of palm fronds, trim the spine zone and cut the base from the midrib. |

Photo 6

|

Photo 7

|

| Palm spines, or thorns, can be 12 inches or more in length. They are three-sided in cross-section and very stiff and strong. | This is the same leaf section viewed from the end. The butt end of the leaf base, as it fell from the tree, and the cut end of the leaf midrib show clearly. The entire leaf was too large to conveniently ship, so Chet Wilcox trimmed it to length, then folded it to gives us a good look at the basic leaf before he makes the final trimming. |

Photo 8

|

Photo 9

|

|

The grainy butt-end of the palm leaf is rich in cellulose but quite different from woody dicots. There are no annual rings, no solid center. A hard epidermis surrounds a soft, fibrous core consisting of vascular bundles and soft cortex tissue. This butt is also untrimmed. Chet Wilcox trims the end and sides of the base, and cuts them to length. |

The 12-gauge shell provides a reference for the size of the frond butt. This particular butt was approximately eight inches wide but, of course, fronds vary in size. |

Photo 10

|

Photo 11

|

|

Wilcox trims the butt and sides to remove the thorns. He also trims the butt to length for carvers. |

The shape of the trimmed palm frond butt lends itself to the graceful arch of the Pintail, and that just happens to be a favorite for waterfowlers in northern California. |

Photo 12

|

Photo 13

|

| The broad end of the palm frond typically forms the body of the decoy. |

The narrow end usually forms the tail end of the decoy. |

Photo 14

|

Photo 15

|

|

Most of the fibrous tissue was cleanly cut through in this butt. Some of the fibers, seen as light specks, were torn and pushed over as the saw blade moved past. This view provides a good view of the texture and composition of the wood. |

A thumbnail easily carvers a gouge in the core of the palm frond. The wood is very soft and very dusty to work with power tools. |

Photo 16

|

Photo 17

|

|

A plastic dinner knife is easily pushed into the core of this palm frond. |

This close-up shows the torn and bent fibrovascular bundles that make up most of this leaf stem. Surrounding the tough fibers is a mass of enveloping cortex tissue. |

|

MORE PALM FROND CARVINGS...

|

|

Photo 18

|

Photo 19

|

| First in Palm Fronds, Bob Berry, El Cajon, California, Cal Open 2008 |

Second in Palm Fronds, Jerry Harris, Dallas Oregon, Cal Open 2008 |

Photo 20

|

Photo 21

|

|

Third in Palm Fronds, Del Herbert, Chula Vista, California, Cal Open 2008 |

Fourth in Palm Fronds, Tom Christie, Lincoln, Nebraska, Cal Open 2008 |

Photo 22

|

Photo 23

|

| Palm Frond Bald Ibis, R. D. Wilson, Mineola, Texas, Cal Open 2008 | Palm Frond Bufflehead, Byrn and JoAnne Watson, Centralia, Washington, Cal Open 2008 |

Photo 25

|

Photo 24

|

| Palm Frond Grouse, Jeff Compton, Nisswa, Minnesota, Cal Open 2008 | Bob Sutton's classic Pintail |

Photo 26

|

Photo 27

|

|

Bob Sutton's classic Pintail |

Bob Sutton's classic Pintail |